Tētahi Ki Tētahi - Essay

Tētahi Ki Tētahi - Essay

Tētahi Ki Tētahi - Essay

Tētahi Ki Tētahi - Essay

Tētahi Ki Tētahi - Essay

Tētahi Ki Tētahi - Essay

Tētahi Ki Tētahi - Essay

Tētahi Ki Tētahi - Essay

Tētahi Ki Tētahi - Essay

Tētahi Ki Tētahi - Essay

Auckland Pride Festival 2025

Curatorial Substructure

Tētahi Ki Tētahi

Entanglement

___

By Hāmiora Bailey

MIHI

I approached Hina in ceremony as a descendent, calling for permission and direction in entering her domain of ritual knowledge (Kame'elehiwi, 1999; Tangaro, 2007).

I summoned her directly, petitioning her to use me as an instrument to return to the world sacred knowledges that might facilitate healing, emancipation and the restoration of balance. I called to the knowledges as well, acknowledging them as cyclic, alive and inter-dimensional, and invited them to find through me a portal of re-entry into Te Ao Marama (Cajete, 2000; Murphy, 2011; Peat, 1996).

I asked for doorways to open and for people that could assist to be brought forward to me. I asked for any barriers to be removed.

— Ngāhuia Murphy (2011)

Content:

- Introduction

- Membership

- Theme

- What is Entanglement?

- Arriving at Tētahi Ki Tētahi

- Vā Moana – The Relational Space of the Ocean

- The Importance of Hina

- Hina Today

- Honouring Hina, Honouring Communities

- Tētahi Ki Tētahi: Entanglement in Practice

- Neke Moa: Embodying the Spirit of Entanglement

- Why is Entanglement important?

- Closing

- Whanaungatanga as Praxis

- Embodying the Work of Tētahi Ki Tētahi

- Entanglement: A Relational Framework

- Decolonization as an Ongoing Process

- Collective Liberation and Queer Futurity

- A Call to Artists, Event Organisers, Activists, and Advocates

Introduction

While there are many overlapping and important citations shared within the following pages, before we begin, it is important to note explicitly one seminal work that has shaped my curatorial philosophy and programming methodology at Auckland Pride for the past 4 years now. Like how Hine-ahu-one was born of Papatūānuku at Kura Waka, made corporeal first and then pneuma and cerebral through a series of incantation, haka, waiata and finally hongi, amalgamating Te Ira Atua and Te Ira Uwha begetting Te Ira Tangata—a process that continues within each new human life conceived (Ihimaera, 2023)– our festival each year is reanimated through the the same life force and mauri given by our teachers and foremothers Hanna Burgess, Donna Cormack, and Whaea Pāpārangi Reid in their kōrero Calling Forth Our Pasts Citing Our Futures (2021).

Oftentimes whakapapa is referred to as our genealogical pasts, however in the context of my time Auckland Pride, we imagine each annual festival offering to be the next layer of a continuing foundation. Like how the lines within an exposed cliff face map the stratigraphy of our whenua, each new festival becomes the new sedimentary layer contributing to the superposition of our enduring whakapapa as an organisation. Through this acceptance and praxis of iteration and growth, of course we honour our genealogical pasts of Hero and Auckland Pride’s establishment in 2013. Thereafter, through delivering each new festival we are empowered to strive forward towards Queer Futurity through being in good relation (Muñoz, 2009). As offered by Burgess, Cormack and Reid (2021):

As Māori, our existence is expansive, layered through whānau, hapū, and iwi intergenerationally (Mikaere, 2017). We are points where our past and future generations meet, points at which past generations reflect into and through to future generations (and vice versa)—points of intergenerational dialogue. As meeting points between generations, we have the ability to shape how reflections of the past refract through us into the future. In doing so, we can shape the future. Through whakapapa, we have a responsibility to shape the future well, to nurture and enhance these intergenerational relationships (Burgess & Painting, 2020). This is the foundation of our knowledge systems—Mātauranga Māori (Royal, 2009).

As Calling Forth Our Pasts Citing Our Futures serves as both the bedrock and methodology to Auckland Pride’s curatorial approach; our festival hopes to demonstrate the profound importance of whakapapa as a citational practice—an act of calling forth genealogies that transcends only ancestry, with each theme setting the foundation for programs and activations that embody intergenerational knowledge, living memories, stories, and experiences that shape and sustain our sense of belonging. In this context, whakapapa is an investiture; it is a living, breathing practice of citation that connects past, present, and future through the duty of maintaining continuous dialogue shared through intentional relationship. Here we enact the keen duty of meaningfully relating known as whanaungatanga.

In centring whakapapa, we conceptualise citations as extensions of our relational world and as a way we can acknowledge and nurture the intergenerational relationships that constitute who we are, and how we come to know. Citation is an expression of whanaungatanga.

This is pertinent for us at Auckland Pride as a membership organisation that is made up of many different people each with our own lived experiences, cultural backgrounds and determination towards queer futurity.

Within this unique makeup of our structure, created and sustained through membership, governed by an elected board and operated through the holarchy model of our leadership team, it is crucial that we continue to ask ourselves whose knowledge systems we are replicating, how we are responsible and accountable to our locality, whose living memory we are validating as true historical sources, and what futures we are calling forth into the present through programming and the allocation of our limited resource. We have a responsibility to ensure that each activation, performance, club night, exhibition, gathering and march within Auckland Pride Festival performs a key role, not of advertising or promoting Queer people and culture to external audiences and the general public— extracting from counter cultures to reveal often personal and vulnerable histories. But instead, that through working together with many diverse communities throughout the month, we are tilling fertile soil to ensure safety through meaningful intergenerational relationships to understand better how we can continue to serve one another as we navigate the loaded and often violent overlapping consequences of cis-heteronormative cultural hegemony as a result of settler colonialism and western imperialism.

As a Pride festival within Aotearoa, a motu (island) within Te Moana Nui A Kiwa (the Pacific Ocean) our liberation is perhaps closer than we realise, with world leading demonstrations from Kura Kaupapa Māori and other Kaupapa Māori frameworks to explore and employ for our communities. Enhanced further by the prioritisation of the natural environment within Tikanga Me Ona Reo Māori, Tā/Vā methodologies and other localised Moana Based Knowledge systems within Hapū. It is within these generative frameworks that we can nobly acquire the prior knowledge through the evolution that naturally occurs within tuakana-teina models within hāporitanga, hapūtanga and collective whānau structures.

That is why the within our methodology the senior artist model is not merely a curatorial fantasy to work with a regarded and renowned practitioner, but moreover it is a culturally relevant convention that grants an opportunity to meaningfully engage with a defined practice that has been developed and mastered over a lifetime, to share these explorations generously with our audiences and communities and to explore the queerness of this practice and the wisdoms it holds for our collective liberation.

While each year the theme of our festival will change to highlight the most pressing needs of our Takatāpui and Rainbow communities, capturing this within the zeitgeist afforded through each years festival as its own temporality, Calling Forth Our Pasts Citing our Futures and our senior artist model will remain constant - to sustain and transform our collective memory as members of these communities and to better inform our ways of being, knowing and doing as an organisation.

Membership

As a Te Tiriti led Rainbow Organisation, we understand that Queerness is not a monolith, our goal at Auckland Pride is not to be the sole authority on history or consequence, but instead to allow the coalescence of many unique and autonomous communities within our ecology to achieve better confluence, consent and creative solutions together towards self determination, liberation and queer futurity. Within this acknowledgment of self-determination we recognise that often unique communities within our wider Kāhui Takatāpui and Rainbow Community share aspirations. However, we are not shy to acknowledge that—based on each having their unique historic and political contexts; resulting in specific and often separate needs— many communities may have aspirations that are independent, or even at odds. To function effectively Auckland Pride must be rooted in our methodology to service our open access festival and our own programmed artists and producers. To maintain equity and cohabitation, it is important that we position ourselves as caretakers of our shared queer ecology, however seeing ourselves as a Taumata, a place that our members, artists, event organisers and audiences return to often, it is crucial that this custodianship is shared alongside you all, as members. As it is within the potentiality of a strong and engaged membership that we can truly utilise our power through a defined and affirmed identity.

Theme

This is why the theme Tētahi Ki Tētahi is being offered for the 2025 Auckland Pride Festival. As it has provided a fertile and necessary takiwā (sanctuary) for us as a new leadership team in how we have come together as individuals, each with our own complicated and varied relationship with Pride, sharing strategic vision and responsibilities to strengthen the organisation and its long term impact. Moreover, it enables us as a unit to make sense of the many relationships we have inherited and are positioned within now as the key operating force within the organisation. Tētahi Ki Tētahi or “to one another, and each other” as it is often translated, is perhaps as much of an instruction to Auckland Pride as it is a theme that we are sharing outward to our community. In it we are continuing to ask ourselves; how it is that we receive and empower each unique relationship that we are entangled within—as an organisation and as people—and how it is that we honour them meaningfully, intentionally and safely.

For the truth is—whether our aspirations for queer futurity and liberation are shared, separate or at odds, as individuals who share our civility within the Tāmaki Makaurau as waewae tapu and our collective identity under our wider Queer Culture with Auckland, we are deeply entangled to one another by sheer proximity alone. Therefore, it is in the mapping, massaging, tending, tracking, following, stitching, releasing, unwinding and lashing of these entanglements that Auckland Pride, our membership, their communities, and our audiences are able to understand how we can better engage with ourselves and each other. In these strands of entangled cosmologies and heavenly bodies, each burgeoning with the potentiality for queer futurity, Auckland Pride is able to execute our key role, not of ownership but of kaitiakitanga. Through better understanding the needs of each other and the strengths, roles and responsibilities of the many who make up our whole, Auckland Pride is better positioned to advocate upstream, beyond the takiwā of our own Kāhui Takatāpui and Rainbow Communities, to corporates, councils, government, funders, patrons, arts organisations, local and international festivals and other institutions, informed meaningfully by the aspirations within our communities that are shared, aware of the boundaries of the aspirations that are independent, and empowered strictly in the knowing of the aspirations that separate.

While it will take more than one festival for us to build trust within our membership and the communities they belong to, to share vulnerably and authentically with us - Tētahi Ki Tētahi grants a permission towards this level of intimacy as our closest horizon. For what Tētahi Ki Tētahi asks each of us to do, is to recognise within each of our own entanglements, the safety in high consent and trust frameworks. By doing this each of us may come to know who we are in our mana (strengths), what our role is within the wider collective and the capacities in which we can collaborate. And in this knowing, we too may come to understand, who our collaborators are in their mana (strengths), what their roles are within our collective, and what capacity they have within our shared aspirations. For it is not within the constant need for homogeneity, but in the unique celebration of equity that we can each achieve more together. When we see each other and our communities for their unique contexts, cultural phenomena and embodied practices, that we can each hold and omit, we are better able to define what collaboration looks like, if it is necessary, if it is healthy and if it shall continue.

What is Entanglement?

In the beginning, there was Te Wehenga—the separation of Ranginui and Papatūānuku. Their embrace was so tight that it cloaked the world in darkness. When their children forced them apart, light flooded in, and the world as we know it began to take shape. But even in their separation, Ranginui and Papatūānuku remained deeply connected. The tears of Rangi fall as rain, nourishing the earth, while the mist rises from Papa to meet him. This story, so integral to pūrākau Māori, is a profound metaphor for entanglement. Though they were physically pulled apart, their love and influence continue to shape and sustain the world around us today.

Te Ao Māori offers profound insights into the nature of entanglement, but Western scientific thought has also developed its own frameworks for understanding this concept. Karen Barad, a leading thinker in quantum physics and feminist theory, explores entanglement through her teaching on agential realism. Barad’s work challenges the idea that entities are separate, self-contained objects. Instead, she argues that entities do not preexist their relationships; they come into being through their interactions with one another. In other words, things exist in relation, not isolation—a core idea also present in Te Ao Māori and other Indigenous cosmogonies.

In quantum mechanics, entanglement refers to a phenomenon where two particles, once connected, remain linked no matter how far apart they are. A change in one instantly affects the other, even across vast distances. This principle defies our common understanding of space and time, revealing that separation does not mean disconnection. As Barad explains, “entanglements are not simply connections but are integral to the very nature of existence.” We exist because we relate. This challenges the traditional Western view of entities as independent and self-sufficient, offering instead a more nuanced understanding of the world as deeply relational.

Barad’s agential realism goes further by suggesting that relationships are not passive or external but active and constitutive. Entities are intra-actively produced through their entanglements with the world. Confirming what Māori have always noted about Te Ao Hikohiko in Meeting the Universe Halfway, “We are part of the world in its ongoing reconfiguring.” This idea resonates with the relational nature of whakapapa in Māori and Pacific thought, where identity and existence are understood not as isolated but as continuously shaped by relationships with people, the environment, and the cosmos.

Barad's insights allow us to see entanglement not just as a physical or scientific phenomenon but as something that applies to our social, cultural, and ethical lives. Just as quantum particles remain connected across distances, so too do our relationships, histories, and communities remain entangled across time and space. Barad's concept of intra-action mirrors the ways in which Moana-based cosmologies describe the interconnectedness of life, in the words of Moana Jackson whakapapa is a series of never ending beginnings. In both cases, entities are not separate but are constituted through their relationships. This offers a powerful framework for rethinking how we understand identity, community, and the contexts and broader systems we navigate as queer people today.

Entanglement, whether viewed through the lens of Te Ao Māori or quantum physics, speaks to the profound interconnectedness that defines existence. These understandings provide opportunities for Takatāpui and Rainbow communities to explore their own identities within a broader, relational framework that embraces diversity, change, continuity, social cohesion and collective action towards concentrated efforts and impact. Similarly, Karen Barad’s agential realism challenges traditional Western notions of separateness, showing that relationships are fundamental to existence itself, even in death.

Both perspectives reveal that entanglement is not a static state but a dynamic process of becoming and re-becoming—one that invites us to rethink how we relate to one another, our environments, and our histories. Whether through the enduring connection of Ranginui and Papatūānuku or the scientific mysteries of quantum entanglement, we are reminded that distance does not sever ties; it transforms them, creating new possibilities for understanding and connection. In a world where separation often feels inevitable, these frameworks offer a vision of Auckland Pride that is deeply relational, constantly evolving, and profoundly interconnected.

Entanglement also speaks to the ways in which we measure and perceive these connections. Even as entities move away from one another, they remain entangled, influencing each other's existence in ways that defy simple explanation. In the same way that a Haka amalgamates the ihi from the individual kaihaka (performers), who each perform to share wehi, their collective impact of the of the group, and be entangled through wana (the aural sphere of projection) to the audience, entanglement arises from the connection of heavenly bodies, who once connected - can never truly be apart again. This idea challenges us to rethink how we understand relationships, not as linear or binary, but as complex, dynamic, and multidimensional.

In this festival, we embrace entanglement as a guiding principle. Tētahi Ki Tētahi—one to another—is more than a theme; it is an acknowledgment of the profound interconnectedness that defines us. As you engage with the performances, art, panels, and discussions throughout the festival, consider the entanglements that shape your life. How do you connect with those around you? How might this change as a result of what you have experienced? How does the separation of Rangi and Papa reflect in your own experiences of distance and closeness to people and place? How might we reimagine our world as one where separation does not mean disconnection, but rather, a different kind of sustaining relationship—one that is deeply entangled, one to another, across the vast expanse of time and space as an ocean of multiple overlapping and colliding potentialities.

Arriving at Tētahi Ki Tētahi

Last year's festival theme, Ki Tua: Beyond Paradise, was a transformative journey that provided valuable insights for our event organisers and artists, their audiences and communities, and Auckland Pride as an organisation. The theme urged us to move beyond the literal and explore the power of pūrākau (myth-making) within personal pakiwaitara (our own narratives), encouraging participants to find merit in our more than human relations, it was a call to embrace storytelling as a means of uncovering universal truths through surrealism, analogy, and metaphor.

The goal of Ki Tua: Beyond Paradise was to foster empathy through imagination, asking artists and audiences to see beyond their immediate reality and apply that vision to the world around them, imagining solutions beyond it. We recognized the power of Jose Estaben Muñoz’ queer futurity, seeing it as permission to create alternate realms. Something our senior artist Rosanna Raymond, and her collectives the Savāge Club and the Pacific Sisters have been doing for years. Acknowledging the personal as political, we invited everyone to dream beyond their current contexts, urging them to tap into the transformative potential of more-than-fiction work.

Central to this theme was the understanding that lived experience, imbued innately with mana and integrity, holds the power to inspire others. We challenged individuals to know their own stories deeply enough to transcend their physical realities, creating pathways for others to engage with those experiences fluidly. As Rosanna Raymond's relationship to Aitu practice reflects and affirmed in her own words:

Here I stand Full Tusk Maiden Aotearoa… kssss aue aue he

Full moons in my horizons, wandering clouds passing by, east to west with soft caress, stained rosy, steeling, the sea shines

Dusky softly I have spoken, as in two the night my home works, as reflective,

subjective, objective, situations are in operation, too much moon shinning, as the sliver delivers…

Deep come the dark, colding

longing the long the longest

the stars shine

Breathed I have bled, when the moon drops past my pants, I look at her in the eye,

golden, slippering, it dropped into my mouth, dripping with fooled mooned horizons

Be aware, urban in fusion, do not be confused by this unison, a class ‘a’

injection, fraction, reaction, orator, orientator, defining, fortification,

exploration, explanation, feet firm, mat laden.

This is where my eyes doth landed, surrounded by eyeland cult’ya

Ki Tua: Beyond Paradise invited us to explore the unseen, pushing the boundaries of what’s possible by blending myth with reality, and in doing so, opened the door to deeper understandings of our own narratives, the responsibility of our collective imagination, and our journeying together towards queer futurity and our shared liberation.

One profound impact from the result of our 2024 Te Tīmatanga residency, was our capacity to celebrate the interconnectedness of cosmological narratives across Te-Moana-Nui-a-Kiwa, lay bare through the shared lived experience and intimate whanaungatanga of Rosanna Raymond and Pounamu Rurawhe and made real at the Civic Wintergarden. These creation stories were inevitably explored in an attempt to remember Muri-Ranga-Whenua as both place and person. In this slow but intentional whakawhanaungatanga, we sought to remember our Ancestress, to meet her, to know her, to learn from her and to love ourselves as extensions of her. As both Māui and Muri-Ranga-Whenua exist within the time of Mā'ohi, our erstwhile existence before arriving in Aotearoa, this process illuminated the complex web of relationships between the divine, the natural world, and humanity, all interwoven throughout Te Moana Nui A Kiwa. In relocating within Muri-Ranga-Whenua and understanding our parental kōrero tuku iho (oral traditions) as Mā'ohi, Ki Tua took us beyond the limited understanding of paradise we often associate with Aotearoa, and revealed the entangled nature of Moana-based knowledge systems through our shared connections as Pacific people to the relations we share with our atua, ariki, environments and to each other.

This is not a new revelation within Kaupapa Māori or Moana Based thought, here it is imperative that we position ourselves firmly within the pepeha of Moana Jackson, in his teachings that:

The tīpuna never forgot that, as much as whakapapa tied us to this land, it also tied us to the Pacific Ocean that we call Te Moana-nui-a-kiwa. When Māui dragged the land from the sea, these islands were known as ‘te tiritiri o te moana’, the gift from the sea, and so they have remained. We also use the name Aotearoa because the islands were bigger than others we may have once known. Yet we never lost sight of the fact that we were still standing on Pacific Islands and that relationships in such a place would always be mediated through a palpable sense of intimate distance.

In this palpable sense of intimate distance, entanglement, as we are coming to understand it, offers a framework that invites us to move beyond the simplicity of linear time and single-threaded narratives. In the context of Pacific cosmologies, the past, present, and future are not separate entities but intertwined threads in a vast, living web. This is affirmed by kōrero shared by Witi Ihimaera in his accounts of the many fish that Māui was able to capture as a result of the jawbone and mātauranga gifted by his grandmother.

The story of the sacred waka doesn't conclude there. Māui was said to have sailed north, east and west on further fishing expeditions. Lo, he fished up tonga. Lo, he fished up the Cook Islands. Lo, he fished up Hawai’i. Lo he fished up Manihiki. Lo, he fished up Mangareva. Māui brought up all the islands of Polynesia from the bottom of the sea before abandoning the waka south of the North Island of Aotearoa.

The world had expanded. One of the names known for Aotearoa was Hawaiki-Tautau, Hawaiki-floating-there. So, with Aotearoa floating in the sea, Hawaiiki-nui, Hawaiiki-roa, Hawaiiki-pāmaomao achieved its mass and its southernmost extension.

Through the pūrākau (mythological stories) of Te Moana Nui a Kiwa, we witness this entanglement in action. These stories are not just historical recounts—they are relational, breathing narratives that shape and are shaped by the people who carry them and continue to tell them.

In last year’s festival, the cosmological connections we explored through the Te Tīmatanga residency were an awakening to the depth of this entanglement. Artists like Rosanna Raymond and Pounamu Rurawhe brought to life creation stories that spanned the Pacific, revealing the shared threads between ancestors, the land, the sea, and our own human existence. Through their work, we came to understand that these cosmologies are not separate from us but are embedded within our very beings, waiting to be acknowledged and become.

What we discovered was that in tracing these stories, we were not merely looking backward, ki tua, beyond. We were unlocking a space where time folds upon itself—where the past informs the present, and the future reaches back to pull us forward. This is the essence of cosmological entanglement, where storytelling becomes a means of seeing ourselves as part of something far greater than the limits of our own lives.

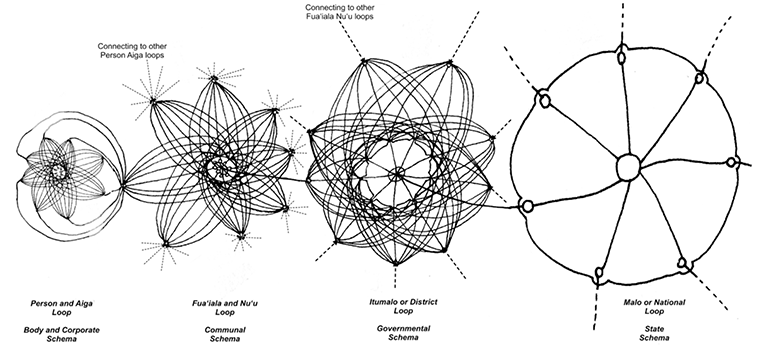

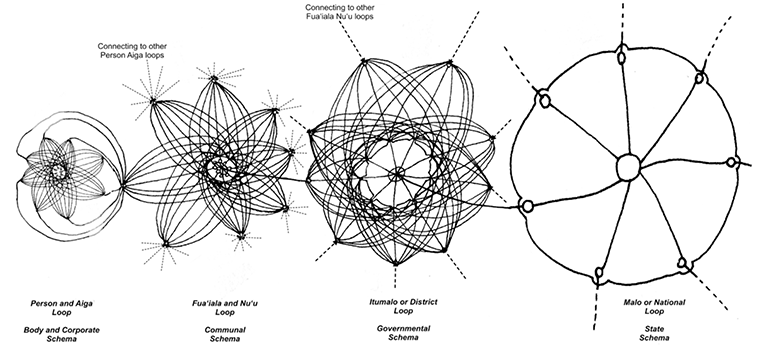

Vā Moana – The Relational Space of the Ocean

Beyond last years festival delivery, we have found great solace in turning to the Marsden Project (2019–2023), Vā Moana: Space and Relationality in Pacific Thought and Identity, as a grounding and fortifying realm to nourish thinking. The Marsden Project (2019–2023), Vā Moana: Space and Relationality in Pacific Thought and Identity, is a groundbreaking research initiative that examines the concept of Vā (relational space) in the Pacific context, exploring how Pacific peoples perceive space, relationships, and identity. Rooted in Pacific indigenous knowledge systems, this project highlights the fluid, interconnected nature of space, time, and human relationships across Te Moana Nui a Kiwa. It challenges Western-centric understandings of space and identity by emphasising the significance of relationality in shaping Pacific worldviews. One of its papers articulates this focus: “The Vā is not merely a physical space, but a lived, dynamic relationship—a sacred and mutual connection between people, place, and time, shaped by both historical and contemporary experiences.” Through this lens, the project reframes how Pacific identities are formed, positioning them as inherently relational and adaptive to both ancestral knowledge, modern contexts and a wider school of thought shared and interrogated across Pacific cultures and their own knowledge systems.

Through the Marsden Project, Te-Moana-Nui-A-Kiwa becomes a relational space that connects all of us—people, land, ancestors, and spirits— within our own islands across the ocean and beyond. Within this research, the concept of vā isn't just about physical space, but about the relationships that exist within it. Like the ocean, these relationships are fluid, ever-changing, and entangled with each other. When we talk about Vā Moana, we're talking about how everything is connected, how our past, present, and future overlap in this vast expanse that carries more than just water—it carries stories, memories, and histories. For Pacific peoples, the ocean is a place of connection, a living space that our ancestors crossed to maintain relationships, share knowledge, and expand community. In our work on Tētahi Ki Tētahi: Entanglement, Vā Moana becomes a powerful realm for understanding how histories and identities weave together, showing that what is unseen and yet to be mapped can still have a profound impact on what we experience today.

This idea of relational space within an ocean of thought, doesn’t belong solely to the Pacific. Within Black and Queer Feminist Theory, Vā Moana echoes similar concepts of relationality that challenge Western ideas of space and time. It speaks to the interconnectedness of people, land, sea, and the cosmos. The idea that we are all entangled, not separate, aligns with how the ocean connects us across time and space, showing that boundaries are not fixed but negotiated and fluid. In this way, the Vā Moana can offer a framework for understanding global entanglement, not just within the Pacific, but as something that connects all of us. It becomes a metaphor for the ways in which our lives—human, animal, land, sea and spirit—are deeply intertwined.

This is where Alexis Pauline Gumbs comes in. Gumbs has written about the ocean as a place of memory, healing, and resistance. She talks about how the ocean is a "dynamic archive of relation and transformation" that holds our histories, migrations, and futures all at once (Undrowned). For Gumbs, the ocean isn’t just water—it’s alive with stories of survival and resilience, particularly for Black communities whose relationships to the ocean are are often rendered within the singular context of the slave trade, have held relationships to the Ocean far before and beyond it. Similarly the Vā Moana reflects this same idea of relationality, where human and non-human experiences are interconnected, creating a larger ecosystem of entangled lives. Gumbs’ work reminds us that we can learn from the ocean itself, from its ability to hold and transform the histories that pass through it. This mirrors how Pacific peoples view the Vā Moana, where the past and future come together in the present, showing us the importance of relationship in shaping who we are.

And it’s not just the metaphorical ocean Gumbs looks to—she draws direct lessons from marine life. In her book Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals, she writes about how sea creatures, who have survived millions of years through cooperation and connection, can teach us about our own survival.

Dolphins know how to travel in masses too. I wonder if responding to violent strictures on human migration and systemic displacement of communities of colour also requires collaboration beyond species. These dolphins travel with other dolphins and with fin and humpback whales in huge groups conducive to safety and collaboration.

These creatures, like whales and dolphins, rely on relationships with each other and their environment to live. For Gumbs, they show us what it means to be in relationship and how vital it is to depend on one another to thrive, she says:

I do commit to rigorously learning how to gracefully collaborate, and step back when it’s your turn with nothing to prove. I do commit to the work of going deep enough to find the necessary food that lights us up inside. I love you, and I have so much to learn. I love you and we are just now learning that it’s possible, love on a scale we can survive. I love you, and how generous—how downright miraculous—it is that life would let me learn like this.

It’s a lesson in entanglement—one that aligns with Pacific ideas of relationality and care, reminding us that survival is not an individual act but a collective one. In looking to the ocean, Gumbs encourages us to rethink our relationships, not just with each other, but with the world around us.

This brings us to the stories of Māui and Hina, figures whose actions reflect different aspects of Vā Moana and entanglement. Māui, the demigod known for his disruptive and transformative deeds—such as fishing up islands and slowing the sun—represents the active, forceful engagement with the natural world. His feats are often framed as acts of control over nature, but they also reveal the deep relationality between humans and the environment. Māui’s actions remind us that change and transformation are part of our relationship with the world around us, echoing the lessons Gumbs draws from marine life. Just as Māui interacts with the ocean and the sun, his actions show that survival and progress require us to engage with and challenge the forces that shape our lives.

In contrast to Māui’s disruptive nature, Hina, Māui’s sister, represents balance, regeneration, and the steady cycles of the natural world. Her connection to the ocean’s tides and the moon’s rhythms highlights the vā between humans and the cosmos. Hina’s presence across the Pacific—whether in Aotearoa, Samoa, Tonga, Tāhiti, or Hawai’i—illustrates how stories adapt based on relationships with the environment, but always emphasize her role in maintaining harmony. In Aotearoa, Hina’s influence on the tides symbolizes the cyclical nature of life, while in Samoa, her stories are tied to love and transformation. In Hawai’i, her ascent to the moon reflects a retreat from earthly burdens, showing how balance is achieved not through domination, but through a return to the natural rhythms of the world.

Together, Māui and Hina offer a complete framework for understanding Vā Moana and the interconnectedness between action and reflection, disruption and regeneration. Māui’s feats of heroism and transformation are necessary for survival, but Hina’s steady influence reminds us that balance and regeneration are equally vital. Like the tides governed by Hina, our relationships with the world must ebb and flow, requiring moments of action and moments of restoration. This dynamic is central to the concept of Vā Moana, where all forces—human, natural, divine—are in conversation with each other, shaping our shared future.

In the same way, Alexis Pauline Gumbs’ work teaches us that entanglement requires both the bold action of Māui and the nurturing balance of Hina. Gumbs’ reflections on marine life show that survival depends on cooperation and care, much like Hina’s role in maintaining the tides. At the same time, the resilience and adaptability of marine creatures echo Māui’s transformative power. Both figures, and the ocean itself, remind us that entanglement is about more than just survival—it’s about evolving together, learning from the relationships that sustain us, and imagining futures that are as expansive as the ocean itself. The Vā Moana becomes a space where queer peoples and all marginalized communities can look for strength, connection, and the possibility of transformation, guided by both Māui’s boldness and Hina’s balance.

So, when we think about Vā Moana and Gumbs’ work together, we see how the ocean becomes a guide, a teacher, and a space where all queer people—especially those of us who have been marginalized—can look for a sense of relationship and futurity. The ocean holds the possibility for healing, for connection, and for imagining new ways of being that are based on care and entanglement. It’s a space that reminds us we are never alone in our journeys, that we are always part of something bigger, something collective. And in that collective space, whether it’s the Vā Moana or the ocean Gumbs writes about, we find not just survival, but the potential for transformation.

The Importance of Hina

As we explore pūrākau this year, following on from Muri-ranga-whenua, it is essential to return back to Hina, Goddess of the moon. Hina connects us to the ocean’s rhythms and cycles, offering another layer to our understanding of Vā Moana, demonstrating how we ought to act within this entangled realm. Her presence across the Pacific shows how stories of balance, love, navigatio, identity and transformation are linked to the ocean. Hina’s connection to the moon and tides reflects the regenerative forces of nature, complementing the disruptive actions of Māui. Hina reminds us that balance is also part of Vā Moana—the space of relationality where all forces, human and natural, are in conversation with each other, shaping our collective futures.

Hina's legacy as a goddess extends far beyond her role as a lunar deity; she is a key figure in Pacific knowledge systems, giving essential skills, informing material culture, and cultural practices that continue to shape our identities today. Hina’s significance in our cosmogonies is woven into acts of creation and transformation, many of which underpin cultural practices within families, villages, hapū, and Iwi. Affirmed in the words of Witi Ihimaera:

Hina-uri in all her identities reached an astounding apotheosis as the warrior empress of the Mā'ohi. Elements of her life history evolved into narratives of their own to be told and retold throughout the empire. Whoever she may have been in reality, the myth took over, and she became multiple goddesses. In Hawai’i she is known simply as Hina, revered for her role as kaitiaki of our world. She became ‘Ina in Mangaia, celebrated in feastal dances and songs that are still performed today.

One such story I remember hearing of Hina growing up was her central role in one of Polynesia’s most well-known stories: the slowing of the sun. Hina, a master weaver, is said to have given her hair to teach Māui the skill of raranga (weaving), a crucial technique that allowed him to create the ropes strong enough to slow the sun. In this tale, Māui's well-known feat in relation to the sun is directly tied to Hina’s knowledge of weaving and the moon’s cycles, emphasising her role in maintaining balance and time. Her hair, symbolising her mana and connection to both celestial and earthly rhythms, becomes a literal and figurative thread in the effort to control the natural world. Without Hina’s contributions, Māui’s success would not have been possible.

Academic Ngahuia Murphy emphasises the deeper relationship between Hina, the natural environment, and restorative praxis within Feminism and decolonisation, noting how her actions remind us of the inextricable link between human life and the cycles of nature. Hina’s gift of weaving is a legacy that persists in the art of raranga today, a practice that is not just an art form but a profound connection to the ancestors and the natural world:

Despite her dominance in pre-colonial Māori society, very little is known of her today. My research has taken me across the Pacific Ocean to the lands of our elders, the Hawaiians, who continue to house her chants and storied landscapes. Whilst examining Hawaiian knowledge related to Hina has deepened this research by providing an Oceanic epistemological framework, it also contextualises the work within the broader political project of decolonising the Pacific.

In various Pacific narratives it is Hina who gifts tapa cloth to humanity, marking her as a key figure in the provision of life-sustaining materials. Tapa, which is still made and worn across the Pacific, is imbued with the sacredness of Hina’s touch, linking her to the cycle of creation and adornment. Last years Senior Artist, Rosanna Raymond, and her Teina Atarangi Anderson have both discussed the significance of tapa as a living cultural material that carries the mana of its origin stories, particularly those tied to Hina's role as a giver of knowledge.

There are many stories of Hina across Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa, sharing similarities that allow us to see her shared importance in the world of barkcloth across the Moana, but also differences that help build a more nuanced and complete picture of her influence. The variations in how she is understood from island to island and, in some cases, from village to village show us her many facets and the different ways wahine drew on her in their life practices

The major themes of her story are outlined below. In te ao Māori, Hina is commonly seen as a personification of the moon, and in some accounts, she is married to Marama, who is the moon (Best, 1922). In Aotearoa, we often refer to Hine-te-iwa-iwa as the auta of all soft fibre; perhaps this is indicative of the material culture in Aotearoa, muka and weaving practices increasing favour over the years due to our colder climate needing a more durable fibre. Regardless, the legacies of aute and her atua Hina lives on through the ways that aute have been used in te ao Māori more generally as a reremembering (Best, 1922).

In Tahiti, Hina became known as Hina-iaa- i-te-marama (Hina who stepped into the moon.) It is believed that the shadows on the moon take the form of branches from the magnificent Ora (Banyan) tree. According to the legend, Hina broke a branch from this tree, causing it to plummet to Earth, where it ultimately became the first Ora. This association with the moon and her role in crafting cloth has earned her the name Hina-tutu-ha’a (Hina who beats cloth), positioning her as the guardian of all the aute makers (Henry, 1985) .

In the Cook Islands, Ina (Hina) is the daughter of Kui the Blind. Ina was a famous barkcloth maker, and Marama falls in love with her and brings her to live on the moon. Ina’s cloth is seen in the white clouds of the heavens (Best, 1976a). In reference to the Tongan goddess Hina, Tevita’ O Ka’ili (2019) explains, “The moon is her abode, and she beats her tapa on the moon as the master artist of nimamea’a koka’anga, the fine art of tapamaking. Women tapa-makers perform a sacred ritual to Hina during the process of tapa-making.” (p. 23–24) ‘O Ka’ili also places Hina as the sister of Māui, in Māori and Cook Islands traditions. In Hawaii, Hina is depicted as the mother of Māui, who slows down the sun to allow his mother to dry her kapa in the sun (Westervelt, 1910). Throughout the islands, the names of Sina, Ina, Hina, and Hine live on, the atua who lives with Marama, beating her cloth on the moon.

In gifting tapa and clothing, Hina gave humanity more than just protection from the elements—she gave the tools of identity and expression. Clothing in Pacific cultures is not merely functional; it is a form of storytelling, genealogy, and connection to ancestors. Hina’s gift of adornments ties directly into the larger themes of identity, where what we wear reflects who we are, our connections to the land, and our place in the cosmos.

Hina Today

Hina’s relationship with Māui, her other brothers, and her many husbands, defies Western gender roles and fixed familial hierarchies, offering instead a fluidity that speaks to the richness of gender within the Vā Moana. Sometimes described as Māui’s sister, other times his mother or even his wife, Hina’s role shifts depending on the context, reflecting the relational, rather than rigid, nature of gender and responsibility within Moana storytelling. In contrast to Western binaries of masculinity and femininity, Hina and Māui embody complementary forces, with Māui representing bold, disruptive action and Hina embodying cyclical, regenerative care. Māui’s feats—slowing the sun, fishing up islands—are acts of transformation, but Hina’s power is just as essential within each of these. It is Hina who teaches Māui how to weave, it is Hina who loves the Eel into submission, it is Hina who domesticated the kuri, it is Hina who illuminates the tides for navigators via the light of the moon. Together, they illustrate that individual roles and responsibilities are fluid, adaptable, entangled for the needs of the collective, rather than being bound by static and polar gender norms.

For Takatāpui and Rainbow Communities in Auckland today, Hina offers a powerful model for understanding one’s place within the collective. Hina’s shifting roles—whether mother, sister, or wife—highlight that our responsibilities to each other are not defined by rigid categories, but by what the community needs in a given moment. Affirmed by the teachings of Atarangi Anderson ‘as we continue to make, we can embody our tīpuna through the process of making. We must draw from the deep and insightful knowledge of the generations before us, which has been (and continues to be) developed, reviewed, refined, and expanded upon over generations (Moana Jackson, 2016), imbuing the works with mana as knowledge tools for re-remembering for future generations.’

The tale of Hina grounds Auckland’s queer culture in the Pacific, offering a distinctly local and Indigenous lens for understanding gender, role, and responsibility. Where predominant queer culture often draws from the experiences, language and progeny of Black and Latinx women in America, we must also turn to our own stories—our own ancestors—for guidance. Hina’s story speaks to the heart of Pacific relationality. She is a figure who embodies not just femininity but the deep wisdom of whakapapa, showing us that our connections to each other, to our ancestors, and to the land and sea are where our power lies.

For Auckland’s Takatāpui and Rainbow communities, Hina invites us to embrace the fluidity of our roles and to understand our individual duties as part of a larger collective responsibility. Hina’s relationship with Māui shows that balance and regeneration are just as important as bold action and transformation. In the context of queer culture, where so often the emphasis is on breaking boundaries and creating new futures, Hina reminds us that care, reflection, and the steady rhythms of life are equally vital. We can look to her for guidance on how to nurture ourselves and our communities while also challenging the forces that seek to confine or limit us. She reminds us that our identities, like hers, are not fixed but interconnected and relational, tied to the rhythms of the moon, the tides, and the histories of our people, and our place within the Vā Moana. In a time where the push for visibility and progress can feel urgent, Hina offers the wisdom of balance, regeneration, and care—qualities we need to sustain ourselves and our communities as we move forward. Let her story guide us in our journeys, not as a distant myth but as a living framework for how we can be in relationship with each other, grounded in the Pacific and the ancestral wisdom that flows through us all.

Honouring Hina, Honouring Communities

As Witi Ihimaera (2023) put’s it “there’s one cycle that is often overlooked. It is the story of Māui’s sister: Hina.” Hina’s frequent erasure within popular narratives reflects the violent institutionalisation of the Western missionary ethic, and its role in defining how we speak to ourselves as Takatāpui and Rainbow Communities today. As it was often missionaries who recorded our pūrākau and offered them to “history,” in continuing to imagine our traditions through a male dominant lens we perpetuate transphobia and homophobia, further imbedding the missionary ethic within contemporary common thought (Murphy, N 2011). Therefore, as Takatāpui and Rainbow Communities striving towards queer futurity, we have a clear role in restoring our matriarchal power within how we express our cultural identities, making honouring Hina within Tētahi Ki Tētahi a crucial act of queer futurity and decolonisation. Here we look explicitly to the teachings of Ngāhuia Murphy in her teaching Te Ahi Tawhito, Te Awhi Tipua, where she notes:

This bond between the genders is also immanent in the sacred story cycles of the primordial parents Ranginui and Papatuanuku who clung to one another as 'one deity', reinforcing notions of gender balance (Pere, 1982, p. 8). It is further demonstrated in historic accounts recorded by Ani Mikaere (2017a), in the recollections of Waikaremoana elder and tohuna tipua, Rangimarie Pere (1982), and in ritual histories surrounding the ceremonies of the whare tangata that I examine in earlier work (Murphy, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2016). Dominance and subordination do not feature in traditional chants (Murphy, 2013; Pere, 1982). Breaking the bond between tānes and wāhine as tribal sisters and brothers who took up arms and fought side by side in the sovereignty wars, was paramount in ensuring the success of the new colonial regime. The process of fracturing the delicate balance between tane and wāhine began with the corruption of the sacred story cycle, which provided the template of social relations (Mikaere, 2017a; Pihama, 2001; Yates-Smith, 1998).

Through honouring Hina as both creator and teacher, we not only acknowledge her contributions to art, culture, and knowledge but also reinforce the importance of feminine power in shaping the world. Hina's story challenges the male-centred narratives that often dominate cosmology, offering a fuller, more nuanced understanding of Pacific cultural identity. Here Tētahi Ki Tētahi: Entanglement echoes the original pūrākau from where its name is derived. Like how Ranginui and Papatūānuku are deeply entangled in their separation, Hina and Māui are entangled through their proximity. Following in teachings of Witi Ihimaera:

Undoubtedly, Hina-uri’s story is as ancient as the stories of her brother Māui-pōtiki. The narratives are mind boggling in their extent, variation, miraculous retellings and reimagining. they comprise a unique repository for us a huge body of fragmented glimpses into one woman's transformation Through Time history and geography. she was a girl who wrote her own narrative within Mā'ohi pūrakau. From sister of demigods and wife to Tangaroa’s son to mother of Tū-huruhuru, she rose to become Hina-of-the-many-names primarily as Hine-te-iwaiwa, patron of women. Indeed her functions blended with the goddess Hine-te-iwaiwa, earlier born from Tane’s mating with Hine-rau-moa, the smallest, most fragile of stars. The two are interchangeable today, both present in charismatic roles as spiritual guardian of all wahine, childbirth, cycles of the moon and the art of weaving.

Entanglement reminds us that the spaces between us are not empty but filled with potential. In the Vā Moana, we find the meeting points of the physical and spiritual, of land and sea, of past and present, of Māui and Hina, Tāne and Wāhine. In the words of Ngāti Porou scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith,

Each individual story is powerful. But the point about the stories is not that they simply tell a story, or tell a story simply. These new stories contribute to a collective story in which every indigenous person has a place... The story and the storyteller both serve to connect the past with the future, one generation with the other, the land with the people and the people with the story.

It is in these relational spaces that entanglement comes to life, and where art finds its most potent expression. If the Vā is a reminder that the boundaries we often think of as fixed are in fact porous, fluid, and alive, entanglement is perhaps a mechanism of accessing or exploring it. Here there is the potential of liberation for each of us, found through acknowledging the dark sides of the moon within ourselves that need acknowledgement and restoration. Finding balance within the disruption of our constant response to settler colonialism, and offering cycles for restoration, peace and rest, ultimately strengthening and sustaining our necessary activism and retaliation.

Our festival, through the framework of Tētahi Ki Tētahi: Entanglement, creates an intentional methodology for honouring Hina's story as a demonstration for how Auckland Pride as an organisation may be able to establish deeper connections between people, histories, and environments that we may have historically overlooked.

It must be said that Hina’s ability to bring balance, regeneration, and protection is not dependent on our acknowledgement of her, much like how there are many unique communities within our wider Kāhui Takatāpui and broader Rainbow Communities who continue to find solutions for themselves and work towards liberation within their own work, with or without the explicit recognition of Auckland Pride. Through honouring Hina within Tētahi Ki Tētahi, we can prioritise establishing a space where the vā between individuals and groups is nurtured, and the entangled relationships between identities and community groups are fully respected. This approach not only celebrates diversity but strengthens the bonds within our collective memory, creating a model for how deeper connections can be made between our communities, histories, and futures.

Auckland Pride can use this honouring of Hina as an embodied practice, ensuring that each community, but particularly brown and black women, feels seen, heard, and celebrated in their uniqueness. Like how the domain of Hina, our moon, waxes and wanes, Tētahi Ki Tētahi allows us to sit within the fullness of her light, realising pride as an abundant time of our closest proximity to one another and each other. The festival’s acknowledgment of Hina’s transformative and relational power serves as a foundation for offering all communities the intimacy, care, and respect they need to feel truly embraced within the vā of Pride, where boundaries are porous and relationships thrive.

Tētahi Ki Tētahi: Entanglement in Practice

At Auckland Pride, the theme of Tētahi Ki Tētahi—one to another—invites us to consider how our identities, stories, and relationships are intertwined. Through the frameworks offered by Refiti, Crenshaw, Jackson, Tui Atua, and Smith, we can begin to understand entanglement not as something to resolve, but as a dynamic and complex space to navigate with care. Whether through the practice of whakapapa, whanaungatanga, or manaakitanga, we are called to engage with our shared entanglements, recognising the interconnectedness of our lives, histories, and futures.

As we move through the festival, we encourage artists, organisers, and participants to reflect on how these frameworks can shape their work and interactions. How can we honour our entanglements, even when they are challenging? How can we create spaces that nurture these connections, making them sources of strength, resilience, and liberation? By engaging with these methodologies, we move closer to a future where Queer Futurity is not just imagined but realised—a future where our collective relationships are the foundation for liberation and abundance.

Neke Moa: Embodying the Spirit of Entanglement

I noho ana au ki te paeahu o te wāhine te mātāwai o te puna kōrero.

Many theorists and academics have sought to explore and articulate the concept of entanglement, offering intricate frameworks for understanding how our lives, histories, and identities are intertwined. While these scholarly contributions are invaluable, for some art can offer a simpler, more immediate way to embody and communicate these connections. Through the physical act of creation, art becomes a living practice of entanglement, where meaning is not only expressed but felt and experienced. It is through art that complex ideas can be shared in ways that transcend language, allowing individuals to connect deeply with both personal and collective narratives.

Neke Moa (Ngāti Kahungunu ki Ahuriri, Kai Tahu, Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Tūwharetoa) is a renowned contemporary jewellery and adornment artist from Aotearoa (New Zealand). Her work, deeply rooted in Māori culture, predominantly features pounamu (New Zealand jade) and other materials gifted by the natural world. Through her art, she promotes hauora (well-being) by exploring connections between tāngata (people), atua (deities), and the environment. Her practice reflects a balance between customary and contemporary processes, creating pieces that act as vessels of cultural memory. Moa has exhibited widely both in Aotearoa and internationally, including significant participation in projects such as the HANDSHAKE project, Wunderrūma, and the Festival of Pacific Arts. Her work has also been shown in Munich, London, Thailand, and Australia, and is part of collections at prestigious institutions like Auckland Art Gallery and Te Papa Tongarewa. In 2023, she received the prestigious Herbert Hofmann Prize at Munich Jewellery Week, further solidifying her position as one of Aotearoa’s most accomplished adornment artists.

Based in Ōtaki, much of her practice involves gathering materials from the local environment, which she then transforms into objects that tell the stories of both personal and collective histories. Moa also actively shares her knowledge, having taught shell craft in Fiji and Tonga, and her works emphasise the entangled relationships between Māori identity, the land, and ancestral narratives.

This year we sit humbly beneath the footstool of Neke Moa in her role as senior artist, perfectly embodying the theme of Tētahi Ki Tētahi: Entanglement through her craft and vision. By engaging with ancestral materials and techniques, Neke’s creations become powerful expressions of connection between past and present, the cosmos, the collective, the self and the divine. Her pieces are not merely objects; they are living vessels carrying cultural memory, honouring atua and reminding us that our stories are embedded in the symbols and taonga we adorn ourselves with. This act of creating through the lens of entanglement reflects her ability to weave together personal and collective histories, affirming that our identity is shaped by the objects we imbue, craft, wear, and pass on.

Neke’s artistry beautifully mirrors Hina’s legacy as a giver of knowledge and sustenance. Just as Hina gifted the world with the skill of weaving and navigation throughout Te-Moana-Nui-A-Kiwa. Neke reinterprets these cultural gifts into contemporary forms of adornment. Her work speaks to Hina’s influence as a nurturing force who tamed natural elements and turned them into something protective and life-sustaining. By placing Papaira (Divine Femininity) and the role of wāhine kaiwhakairo (female carvers) at the heart of her practice, Neke revives the role of Hina and other Wāhine Atua within contemporary experiences and the dynamic and living relationships with our cosmological frameworks, highlighting how the nurturing, regenerative forces of Hina continue to shape and sustain cultural identity today. Through the materials she uses, Neke channels the cycles of creation and regeneration, much like Hina’s role in the natural world, reminding us that our adornments are sacred symbols of who we are and where we come from.

Neke Moa’s practice illustrates how the personal is always intertwined with the collective. Her creations remind us that individual stories—our pakiwaitara—are part of a larger web of shared experiences, cultural history, and environmental connection. Like a piece of driftwood washed ashore and transformed into taonga (treasure), our personal narratives are shaped by the collective currents of history, community, and environment. Neke’s jewellery serves as a conduit for this interconnectedness, where the act of creation draws upon ancestral knowledge and recontextualizes it within contemporary frameworks. In this way, her work transcends isolation, reinforcing the idea that we are never alone in our stories; our lives are always in conversation with the past and the future, and with the people who came before us and walk alongside us. This is a significant practice positioned within our festival model, as taonga is often gifted, implying a deep sense of reciprocity.

Through Neke’s example, we encourage our event organizers and community members to create altars for themselves and for each other—spaces that hold meaning, connection, and reflection. Rather than allowing the ephemeral nature of the festival to pass over them, we ask: how can we leave something behind? What can we offer to one another as an acknowledgment of our shared journeys, our respect, and our deep entanglements? In this way, each festival event becomes taonga, contributing not only to the identity of Auckland Pride but to the broader community legacy. These events transcend simple performances or gatherings; they are imbued with layers of connection, memory, and belonging. Participating in these moments fosters a reciprocal relationship with the spaces we occupy, the history we honour, and the people who share in these experiences, much like the exchange of taonga, which carries both responsibility and honour.

By recognizing events as taonga, we understand their role in an ongoing conversation that spans past, present, and future. They invite us to engage with the festival’s theme—Tētahi Ki Tētahi—by reflecting on how personal identity is intricately tied to place and community. These events are living, breathing expressions of our collective cultural story.

Artists can further acknowledge these relationships through gifts or gestures that symbolise connection and reciprocity. This could take the form of collaborative artworks, gifting personalised taonga such as jewellery or artistic ephemera and posters to friends and collaborators, or even exchanging culturally significant items to emerging leaders you are supporting within the delivery of your event. Offering written reflections, eating together, and creating rituals around gifting and receiving, and closing Pride month meaningfully through physical adornment and art celebrates the creative process while leaving behind lasting symbols of the relationships and entanglements formed through shared artistic journeys.

Why is Entanglement important?

Art has long played a pivotal role in the liberat of ion movements of marginalised communities, acting as both a mirror and a catalyst for social change. Through artists like Neke Moa, we see how creative expression can embody the principles of entanglement, offering spaces for reflection, resistance, and reconnection. Moa’s work bridges personal narratives with collective histories, grounding contemporary queer experiences in the cultural and cosmological wisdom of the past. Art becomes a living practice that nurtures both identity and community, fostering a deeper understanding of our shared struggles.

However, the importance of this creative resistance extends beyond the gallery and into today’s political climate. As Takatāpui and Rainbow communities continue to face inequities—rooted in systemic discrimination and exacerbated by rising global anti-queer sentiment—the need for collective action and solidarity is more urgent than ever. Art does more than reflect these challenges; it illuminates pathways for resilience and transformation. In a time where political decisions threaten to erode hard-won gains for inclusivity and equality, understanding these entangled struggles allows us to respond with greater clarity and purpose. Alongside offering artistic insights and expressions of Entanglement, Auckland Pride must also offer learning environments where we are able to recognise and address how honouring and utilising our many entanglements is essential in the fight for social justice and equity today.

In Aotearoa, Takatāpui and Rainbow communities continue to face significant inequities, despite ongoing efforts toward greater inclusivity. These inequities are deeply rooted in systemic discrimination and social marginalisation. Recent data shows that these communities experience higher rates of mental health challenges, discrimination, and economic hardship (Counting Ourselves 2022). For instance, younger members of these communities are disproportionately affected by these issues, with many reporting experiences of erasure, rejection, and a lack of affirming spaces. The mental health crisis among Rainbow youth is alarming, exacerbated by societal stigma and the lack of adequate support systems.

Furthermore, the rise in anti-trans and anti-queer sentiment globally has found echoes in Aotearoa, where public figures and organisations have openly challenged the rights and visibility of Rainbow communities. Incidents like the harassment faced by participants in events such as Queenstown’s Winter Pride festival highlight the growing tension between progressive local initiatives and conservative backlash. These challenges are compounded by the broader socio-political environment, where coalition agreements and policies from the incoming government may further marginalise Rainbow communities, particularly through the removal of educational guidelines on gender and sexuality. Such measures risk undermining inclusive practices that have been developed to foster safe, supportive environments for Takatāpui and Rainbow youth, while also curtailing efforts to ensure fairness and equity in sports. This reflects a broader trend, where local governments’ attempts to support diversity—such as through the establishment of Māori wards—are often undermined by national policies that seek to erase these gains. The recent push by the national government to eliminate Māori wards, despite local councils voting to keep them, serves as a stark example of how political entanglements can either support or severely restrict progress towards equity. Such measures not only risk undermining inclusive practices for Takatāpui and Rainbow youth but also challenge broader efforts towards fairness and representation for marginalised communities.

The uncertainty surrounding these changes leaves advocates and community leaders concerned about their potential impact, making it more urgent than ever for Rainbow and Māori communities to mobilise, support one another, and continue to advocate for their rights.

Entanglement theory is vital in this context as it underscores the interconnectedness of these challenges. The decisions made at a national level regarding Māori representation, for instance, are deeply intertwined with the lived experiences of Takatāpui and Rainbow communities. The local councils' fight to maintain Māori wards is not just a political battle but an assertion of the need for diverse voices in governance, which directly impacts how inclusive and supportive our communities can be. In the words of Black Lesbian Feminist, Theorist and Abolitionist, Ruha Benjamin, in her critique of techno-futurism as a tool for white supremacy Race After Technology (2019),

Perhaps most importantly, abolitionist tools are predicated on solidarity, as distinct from access and charity. The point is not simply to help others who have been less fortunate but to question the very idea of "fortune": Who defines it, distributes it, hoards it, and how was it obtained? Solidarity takes interdependence seriously. Even if we do not "believe in" or "aspire to" interdependence as an abstract principle, nevertheless our lived reality and infrastructural designs connect us in seen and unseen ways. This is why, as Petty insists, oppressed people do not need "allies," a framework that reinforces privilege and power. Instead, "co-liberation" is an aspirational relationship that emphasises linked fate.

Moreover, Tētahi Ki Tētahi also helps us understand the less visible, yet profound, entanglements that exist within our social fabric. For example, the inequities faced by Rainbow communities are not isolated incidents but are connected to broader systemic issues such as poverty, housing instability, and healthcare disparities, particularly in regions like South Auckland and Northland, where deprivation rates are high, and access to services is limited. By embracing Tētahi Ki Tētahi, the festival not only celebrates diversity but also acknowledges the complex web of relationships and power dynamics that shape the experiences of Takatāpui and Rainbow communities today. This approach fosters a more holistic understanding of equity, one that is not only about visibility but also about dismantling the structures that perpetuate inequality.

The importance of entanglement theory in this context lies in its ability to illuminate the interconnectedness of our struggles and the necessity of addressing them collectively. It challenges us to see the fight for Takatāpui and Rainbow rights as inherently linked to the broader struggle for social justice in Aotearoa, including the ongoing battle for Māori sovereignty. By doing so, we can work towards a future where we are liberated, thriving and connected.

Closing

As we bring this work on Tētahi Ki Tētahi: Entanglement to a close, we recognize the profound depth of the journey we’ve undertaken, not just as a festival but as a community invested in the relational fabric that binds us all. At Auckland Pride, we are more than just a collection of events; we are a space for interconnected narratives, where past, present, and future are constantly in conversation. This year’s theme, Tētahi Ki Tētahi, has illuminated the intricate entanglements that define our relationships—with ourselves, our ancestors, our communities, and the environment. These connections aren’t merely about proximity; they’re about the unseen threads that link us through shared histories, struggles, joys, and aspirations for queer futurity.

The work of entanglement is ongoing and complex. It’s not something resolved in a single festival cycle but an evolving process. Each action, each performance, and every conversation contributes another thread to the tapestry we are weaving. This year’s festival reminds us that the spaces between us are not empty but charged with potential—spaces where we can find common ground, heal past wounds, and imagine new futures together.

From the outset, we have drawn on Indigenous knowledge systems to guide our work, particularly through Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s 25 Indigenous Projects, Moana Jackson’s 10 Ethics of Indigenous Research, Kimberly Crenshaw’s Intersectionality and Tui Atua Tupua Tamasese’s Four Harmonies. These projects have served as a roadmap, encouraging us to think critically about how we engage with Indigenous communities, decolonize our practices, and honour the histories and identities that shape Takatāpui and Rainbow communities.

Whanaungatanga as Praxis

At the heart of our work lies whanaungatanga, the practice of building and nurturing relationships. Through whanaungatanga, citation becomes an act of honouring those who came before us and those who walk alongside us. It’s not just about ancestry; it’s about how we choose to connect, sustain, and enrich our relationships, contributing to the broader whakapapa of our communities.

Auckland Pride is a living example of this praxis. Our festival doesn't just commemorate queer history; it builds on it. We are part of the ever-expanding genealogy of queer resistance, creativity, and community building. In this sense, we are not only calling forth our pasts—we are actively citing them to shape our futures.

Embodying the Work of Tētahi Ki Tētahi

Tētahi Ki Tētahi has served as both a guiding principle and an instruction this year. It urges us to reflect on how we relate to one another and honour the entanglements within our communities. This is not just about connections between individuals—it’s about the relational systems that nourish or constrain our ability to thrive.

Our liberation is collective. Queer futurity cannot be achieved in isolation; it requires continuous engagement, acknowledgment of our interdependence, and understanding that every action we take has ripple effects across our communities. This concept has been central to everything we’ve done, from open-access events to curated programs centering Indigenous, queer, and trans voices.

Tētahi Ki Tētahi is more than a theoretical framework—it’s practical. It’s about how we show up for each other, the care we extend, and the relationships we nurture. From the senior artist model that allowed experienced practitioners to pass on knowledge to grassroots initiatives creating space for emerging voices, Tētahi Ki Tētahi has informed how we build trust and allocate resources within our membership.

Entanglement: A Relational Framework

Our understanding of entanglement has deepened throughout festival planning. Drawing on Indigenous cosmologies and quantum physics, we now appreciate entanglement as a dynamic process that shapes who we are. Separation doesn’t mean disconnection—it offers new ways to engage with relationships that have shaped and continue to shape our world.

Entanglement speaks to how our identities, histories, and futures are bound together. In Auckland Pride, this means recognizing that every decision we make—every program we curate or partnership we form—has far-reaching consequences. Our task is to navigate these entanglements with care, respect, and an eye toward collective liberation.

This year’s programming, especially through the Te Tīmatanga residency, has shown us that our identities are intertwined with the land, sea, and cosmos. The narratives of Māui and Hina, for instance, teach us that our relationship to the natural world is deeply interconnected with how we relate to each other. These cosmologies aren’t just myths; they are living frameworks offering profound insights into navigating entanglement today.

Decolonization as an Ongoing Process

At the core of entanglement is the ongoing process of decolonization. It’s a task that cannot be completed in a single festival cycle. Decolonization requires continuous reflection, action, and accountability—dismantling colonial structures and replacing them with systems that honour Indigenous sovereignty, self-determination, and collective care.

At Auckland Pride, we have used Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s 25 Indigenous Projects as a guide to reclaim and restore Indigenous knowledge systems. Whether through creating space for Indigenous voices, celebrating community survival, or remembering histories of resistance, decolonization has been integral to our work this year. It’s an ongoing effort to ensure that power is redistributed to those who have historically been marginalized.

This process also involves examining our own organizational power structures. We continuously ask who holds decision-making power, whose voices are centered, and how we ensure our work isn’t just inclusive but actively redistributive.

Collective Liberation and Queer Futurity

Entanglement and decolonization are about collective liberation. Our vision for queer futurity is relational—requiring us to build systems of care and mutual support, to reflect continuously on how we create spaces that are inclusive, equitable, and just. Tētahi Ki Tētahi will continue to guide us, shaping how we engage with one another and honour our entanglements.

As we move forward, the work of entanglement will weave through everything we do. This year’s festival has shown that relationships—whether personal, professional, or cosmological—are dynamic and constantly evolving. This is the work we carry forward into future festivals and beyond, shaping a future where queer liberation is deeply interconnected with the lives, histories, and futures of all who journey with us.

A Call to Artists, Event Organisers, Activists, and Advocates

As we prepare for the journey ahead, we invite artists, event organizers, activists, and advocates to become members of Auckland Pride. Our work thrives through the collective energy and contributions of our community, and membership is a powerful way to engage in shaping the future of our festival and beyond. By becoming a member, you’ll be part of a growing, diverse collective that values equity, inclusion, and the strength of our shared entanglements. Membership offers an opportunity to have a say in how Auckland Pride operates, to be part of the decision-making process, and to collaborate with others who are equally committed to queer futurity and community empowerment. Together, we can continue to build spaces where everyone feels seen, valued, and celebrated in their unique identities. Now more than ever, your involvement matters. By joining Auckland Pride, you are not only supporting the work we’ve done but contributing to the future we are creating, Tētahi Ki Tētahi, one to another.

As we close, we do so with a firm understanding that our work is ongoing. The threads of entanglement will continue to shape Auckland Pride and the communities we serve far beyond the delivery of the 2025 festival. In this, we find hope, strength, and the promise of a future where queer liberation is a lived reality, entangled with the lives, histories, and futures of all who are part of this journey. Together, we will continue to nurture these relationships and build a future grounded in mutual care, accountability, and shared vision.